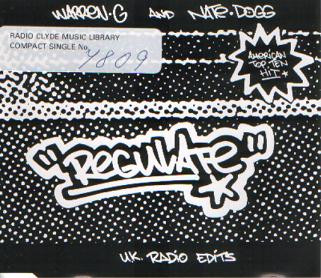

Warren G & Nate Dogg - Regulate UK Radio Edits

Table of Contents

Download

Filename: warren-g-nate-dogg-regulate-uk-radio-edits.zip- MP3 size: 16.5 mb

- FLAC size: 140.1 mb

Tracks

| Track | Duration | Preview |

|---|---|---|

| Regulate (Radio Edit Part Intro) | 3:57 | |

| Regulate (Radio Edit No Intro) | 3:49 | |

| Regulate (Radio Edit Full Intro) | 4:09 |

Video

Warren G - Regulate (Official Music Video) ft. Nate Dogg

Images

Catalog Numbers

A8290CDDJLabels

Death Row Records , Interscope RecordsListen online

- ascolta in linea

- lytte på nettet

- escuchar en línea

- écouter en ligne

- online luisteren

- ouvir online

- kuunnella verkossa

- lyssna på nätet

- online anhören

Formats

- CD

- Single

- Promo

About Warren G & Nate Dogg

Warren Griffin III (born November 10, 1970 in Long Beach, California) more commonly known as Warren G, is an American West Coast rapper and hip hop producer. His biggest hit was the single "" with released in 1994. The single was a g-funk track like most of Warren G's productions. He is the step-brother of successful record producer . According to Hit Music he sold 1,080,000 copies in the UK between January 1990 - January 1999 so he was ranked 92nd amongst the top selling artists of the decade.

In 1991, Warren G formed the group with Nate Dogg and . Warren G introduced the group to his step-brother Dr. Dre. Dr. Dre was impressed and signed Snoop Dogg to his and Suge Knight's record company, . Thus, 213 broke up before releasing any records, and the three artists pursued separate careers. Even though Death Row Records did not sign Warren G, his career began with some contributions to Dr. Dre's album The Chronic, released 1992. Warren G was a regular contributor to many Death Row albums.

In 1993, Warren G produced the track "

Real Name

- Warren Griffin III

Name Vars

- DJ Warren G

- Griffin

- W

- W. Griffin

- Waren G

- Waren G.

- Warren

- Warren \

- Warren G Productions

- Warren G.

- Warren J

- WarrenG

- Warreng

Aliases

- Warren Griffin III

Comments

2023-04-12

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9gbQVj4MR3M&ab_channel=RHINO

2023-04-12

Can't forget gangsters paradise Coolio you rock that song

2023-04-12

Me and my uncle used to listen to this song all the time before he killed himself miss you bro

2023-04-12

My 6 year old was like daddy i love this song…she listens to it almost daily..lol .. for ever classic

2023-04-12

Can't beat the 90s

2023-04-11

nate was so smooth and flowy

2023-04-11

Suge regretted not signing Warren G

2023-04-10

I'm listening Feb 2023

2023-04-10

Who else knows all the lyrics, from listening to this song so much growing up?!

2023-04-10

Classique universelle ❤️

2023-04-10

Old school

2023-04-09

2023

2023-04-09

Facts

2023-04-09

Got me thinking bout the old days

2023-04-08

Stole the melody from Steely Dan

2023-04-07

Inspired to listen to this after Axel says "regulators! Mount up" in Van Helsing (season 3, episode 5). Sad that so many people won't know this reference.

2023-04-06

Always. Every day

2023-04-05

What a strange censor for 'clip' and 'cold' and well 'gat' too wtf? Nigga, bitch, pussy, fuck all cool but don't say clip, cold or gat!

Edit: This has to be the like the Carson Daly TRL version.

Edit: This has to be the like the Carson Daly TRL version.

2023-04-05

Wog Dogg

2023-04-04

Remember this, and show yourselves men;

Recall to mind, O transgressors.

Remember the former things of old,

For I am God, and there is no other;

I am God, and there is none like Me,

Declaring the end from the beginning,

And from ancient times things

that are not yet done,

Saying, "My counsel shall stand,

And I will do all My pleasure,'

Calling a bird of prey from the east,

The man who executes My counsel,

from a far country.

Indeed I have spoken it;

I will also bring it to pass.

I have purposed it;

I will also do it.

Recall to mind, O transgressors.

Remember the former things of old,

For I am God, and there is no other;

I am God, and there is none like Me,

Declaring the end from the beginning,

And from ancient times things

that are not yet done,

Saying, "My counsel shall stand,

And I will do all My pleasure,'

Calling a bird of prey from the east,

The man who executes My counsel,

from a far country.

Indeed I have spoken it;

I will also bring it to pass.

I have purposed it;

I will also do it.

2023-04-03

Christianity and Buddhism Contrasted

At the end of such a long discussion on salvation in Buddhism it is

very tempting to try to determine which religion—Buddhism or Christianity—is a “better” option for salvation. The fact that I am writing and

living as a Christian is an indication of which option I have chosen as

my own solution to life. A far more important and significant question in

the context of Christian mission should be how to build a bridge to make

salvation attractive and understandable to Buddhists. Dean Halverson in

his book The Compact Guide to World Religions (1996) has contrasted Buddhism and Christianity in order to show some of the large intellectual and

spiritual differences and, therefore, barriers that exist between both systems—in regard to God, humanity, the problem (of sin); the solution and

the means to solve this problem; and the final outcome (see Table 2). The

most striking difference is that in Buddhism human beings are “on their

own.” There is no power beyond themselves, and Nirvāna is the “end” for

Buddhists. In contrast, heaven is the beginning of something more glorious for Christians.

Buddha and Jesus

The founder of Buddhism clearly had a beginning and an end. The

Siddhharta Gautma was born as a prince into a wealthy Hindu family.

Though he achieved his “Great Enlightenment” through meditation and

became “The Enlightened One” (or the Buddha), he finally reached his

end, he is no longer alive. Unlike the Buddha, Jesus is the “The Ancient

of Days,” who has no beginning or ending, one who is the truth and does

not need further enlightenment (Col 1:15-20; John 1:9-14, 17; 17:3; 20:31;

Rom1:4; Jude 1:25; Heb 13:8; Rev 22:13). Because of his special relationship

to God (John 3:16; 6:44; 14:6, 9), reconciliation between God and man can

be achieved through him. Jesus can claim to “be the way” by which salvation and eternal life can be received (John 14:6; 5:35), whereas the Buddha

merely claimed to point to the way by which we could escape suffering

At the end of such a long discussion on salvation in Buddhism it is

very tempting to try to determine which religion—Buddhism or Christianity—is a “better” option for salvation. The fact that I am writing and

living as a Christian is an indication of which option I have chosen as

my own solution to life. A far more important and significant question in

the context of Christian mission should be how to build a bridge to make

salvation attractive and understandable to Buddhists. Dean Halverson in

his book The Compact Guide to World Religions (1996) has contrasted Buddhism and Christianity in order to show some of the large intellectual and

spiritual differences and, therefore, barriers that exist between both systems—in regard to God, humanity, the problem (of sin); the solution and

the means to solve this problem; and the final outcome (see Table 2). The

most striking difference is that in Buddhism human beings are “on their

own.” There is no power beyond themselves, and Nirvāna is the “end” for

Buddhists. In contrast, heaven is the beginning of something more glorious for Christians.

Buddha and Jesus

The founder of Buddhism clearly had a beginning and an end. The

Siddhharta Gautma was born as a prince into a wealthy Hindu family.

Though he achieved his “Great Enlightenment” through meditation and

became “The Enlightened One” (or the Buddha), he finally reached his

end, he is no longer alive. Unlike the Buddha, Jesus is the “The Ancient

of Days,” who has no beginning or ending, one who is the truth and does

not need further enlightenment (Col 1:15-20; John 1:9-14, 17; 17:3; 20:31;

Rom1:4; Jude 1:25; Heb 13:8; Rev 22:13). Because of his special relationship

to God (John 3:16; 6:44; 14:6, 9), reconciliation between God and man can

be achieved through him. Jesus can claim to “be the way” by which salvation and eternal life can be received (John 14:6; 5:35), whereas the Buddha

merely claimed to point to the way by which we could escape suffering

2023-04-03

At the time a violent king named Virudaka of Kosala conquered the

Sakys clan. Prince Mahanama went to the King and sought the lives

of his people, but the King would not listen to him. He then proposed

that the King let as many prisoners escape as could run away while he

himself remained underwater in the nearby pond.

To this the King assented, thinking that the time would be very

short for him to be able to stay underwater.

The gate of the castle was opened as Mahanama dived into the water and the people rushed for safety. But Mahanama did not come up,

sacrificing his life for the lives of his people by tying his hair to the

underwater root of a willow tree. (The Teaching of Buddha 1966:254, 255,

cited in Halverson 1996:66, 67)

This simple story conveys a number of images that can illustrate to

Buddhists (from their own literature) the significance of Christ’s sacrificial

death.

All of us are enslaved—perhaps not to a wicked king but we are in

bondage to sin (John 8:34; Rom 6:6, 16). Through of the death of Mahanama

all the members of the Shakya clan were freed from bondage of the wicked

king and correspondingly, Christ died to free all of humanity from the

bondage of sin (Matt 20:28, Rom 5:18, 19). Mahanama voluntarily died

because he was motivated by love for his people, so Christ also freely gave up

His life out of love for all humanity (John 10:11-18; 13:1, 24). Salvation is not

something we can earn, but it is free for the taking. Freedom from bondage

for the Sakya clan was gained by simply running from the kingdom of the

wicked king. People can receive the gift of salvation by placing their faith

in the atoning work of Jesus Christ (Rom 3:20-24; Eph 2:8, 9) (Halverson

1996:67). Salvation does not depend on our human efforts of doing good

works (such as rituals and merit making in order to achieve “good karma”

(Amore and Ching 2002:232, 233). In fact “all our righteous acts are like

filthy rags” (Isa 64:6).

The reason that as Christians we can face the future with confidence

is the fact that Jesus, our Savior, is alive. His remains are not housed in a

grave or a temple (such as the “Temple of the Tooth” in Kandy, Sri Lanka,

where people come to “worship” the tooth of the Buddha). Christ’s tomb

is empty, whereas the Buddha and other religious founders are dead. Because Jesus is alive we have hope not only for the future but for our daily

living as well.

2

Sakys clan. Prince Mahanama went to the King and sought the lives

of his people, but the King would not listen to him. He then proposed

that the King let as many prisoners escape as could run away while he

himself remained underwater in the nearby pond.

To this the King assented, thinking that the time would be very

short for him to be able to stay underwater.

The gate of the castle was opened as Mahanama dived into the water and the people rushed for safety. But Mahanama did not come up,

sacrificing his life for the lives of his people by tying his hair to the

underwater root of a willow tree. (The Teaching of Buddha 1966:254, 255,

cited in Halverson 1996:66, 67)

This simple story conveys a number of images that can illustrate to

Buddhists (from their own literature) the significance of Christ’s sacrificial

death.

All of us are enslaved—perhaps not to a wicked king but we are in

bondage to sin (John 8:34; Rom 6:6, 16). Through of the death of Mahanama

all the members of the Shakya clan were freed from bondage of the wicked

king and correspondingly, Christ died to free all of humanity from the

bondage of sin (Matt 20:28, Rom 5:18, 19). Mahanama voluntarily died

because he was motivated by love for his people, so Christ also freely gave up

His life out of love for all humanity (John 10:11-18; 13:1, 24). Salvation is not

something we can earn, but it is free for the taking. Freedom from bondage

for the Sakya clan was gained by simply running from the kingdom of the

wicked king. People can receive the gift of salvation by placing their faith

in the atoning work of Jesus Christ (Rom 3:20-24; Eph 2:8, 9) (Halverson

1996:67). Salvation does not depend on our human efforts of doing good

works (such as rituals and merit making in order to achieve “good karma”

(Amore and Ching 2002:232, 233). In fact “all our righteous acts are like

filthy rags” (Isa 64:6).

The reason that as Christians we can face the future with confidence

is the fact that Jesus, our Savior, is alive. His remains are not housed in a

grave or a temple (such as the “Temple of the Tooth” in Kandy, Sri Lanka,

where people come to “worship” the tooth of the Buddha). Christ’s tomb

is empty, whereas the Buddha and other religious founders are dead. Because Jesus is alive we have hope not only for the future but for our daily

living as well.

2

2023-04-02

The End of Suffering (The Third Noble Truth)

Since the Buddhist concept of suffering arises from a person’s clinging

desire (Pali tanhā, Sanskrit samudaya or trishna) to that which is inevitably

impermanent, changing, and perishable, there is a need to end that craving (nirodha) and free oneself from all desire (Burton 2004:22). The Third

Noble Truth deals with the elimination or cessation of the root of dukkha,

which we have seen earlier is “thirst” (tanhā). This is achieved by eliminating all delusion, thereby reaching a liberated state of Enlightenment

(bodhi) and Nirvāna (nirvāna is the more popular Sanskrit term of the Pali

term of Nibbāna).

What is Nirvāna? Extensive descriptions and definitions have been proposed, but most of them have been more confusing than clarifying. The

reason for that is simple, according to Buddhist scholars such as Rahula

(1978:35): “Human language is too poor to express the real nature of the

Absolute Truth or Ultimate Reality.”

Nibbāna is the ultimate goal of Buddhism. It amounts to perfect happiness, the liberation from the cyclic process of dukkha. In early Buddhism

it was considered the highest goal, which every individual ought to attain sooner or later. This ultimate goal is without dispute (Vajiraāna 1971).

However, others have perceived Nibbāna differently. One interpretation

sees Nibbāna as a transcendental reality beyond any form of conceptualization or logical thinking. “It is a metaphysical reality, something absolute, eternal and uncompounded, a noumenal behind the phenomenal”

(Premasiri n.d.:3). Others have interpreted Nibbāna to mean the “extinction of life, an escape from the cycle of suffering which in the ultimate

analysis is equivalent to eternal death” (3). Because of this, many scholars

have voiced the opinion that Buddhism is an “otherworldly,” a “life-denying,” and a “salvation religion” that has nothing to do with this world

(Story 1971; Coomaraswarmy 1975:48).

To call the Buddhist ideal of Nibbāna a concept that is lacking in social

and worldly concerns is only true if by “social and worldly concerns”

one understands the involvement in acts of wickedness, greed, and folly.

Buddhism concentrates on man’s character traits, according to which a

morally good person is a person whose mind feels social concern and will

do what is right as a matter of course (Aronson 1980, especially chapter 6).

The Buddha instructed the first 60 of his disciples who had attained

Nibbāna with the following words: “Go ye forth and wander for the gain

of the many, for the welfare of the many, out of compassion for the world,

for the good, for the gain and the welfare of gods and men. Let not two of

you go the same way” (Vinaya 1:21).

9

Maier: Salvation in Buddhism

Published by Digital Commons @ Andrews University, 2014

Since the Buddhist concept of suffering arises from a person’s clinging

desire (Pali tanhā, Sanskrit samudaya or trishna) to that which is inevitably

impermanent, changing, and perishable, there is a need to end that craving (nirodha) and free oneself from all desire (Burton 2004:22). The Third

Noble Truth deals with the elimination or cessation of the root of dukkha,

which we have seen earlier is “thirst” (tanhā). This is achieved by eliminating all delusion, thereby reaching a liberated state of Enlightenment

(bodhi) and Nirvāna (nirvāna is the more popular Sanskrit term of the Pali

term of Nibbāna).

What is Nirvāna? Extensive descriptions and definitions have been proposed, but most of them have been more confusing than clarifying. The

reason for that is simple, according to Buddhist scholars such as Rahula

(1978:35): “Human language is too poor to express the real nature of the

Absolute Truth or Ultimate Reality.”

Nibbāna is the ultimate goal of Buddhism. It amounts to perfect happiness, the liberation from the cyclic process of dukkha. In early Buddhism

it was considered the highest goal, which every individual ought to attain sooner or later. This ultimate goal is without dispute (Vajiraāna 1971).

However, others have perceived Nibbāna differently. One interpretation

sees Nibbāna as a transcendental reality beyond any form of conceptualization or logical thinking. “It is a metaphysical reality, something absolute, eternal and uncompounded, a noumenal behind the phenomenal”

(Premasiri n.d.:3). Others have interpreted Nibbāna to mean the “extinction of life, an escape from the cycle of suffering which in the ultimate

analysis is equivalent to eternal death” (3). Because of this, many scholars

have voiced the opinion that Buddhism is an “otherworldly,” a “life-denying,” and a “salvation religion” that has nothing to do with this world

(Story 1971; Coomaraswarmy 1975:48).

To call the Buddhist ideal of Nibbāna a concept that is lacking in social

and worldly concerns is only true if by “social and worldly concerns”

one understands the involvement in acts of wickedness, greed, and folly.

Buddhism concentrates on man’s character traits, according to which a

morally good person is a person whose mind feels social concern and will

do what is right as a matter of course (Aronson 1980, especially chapter 6).

The Buddha instructed the first 60 of his disciples who had attained

Nibbāna with the following words: “Go ye forth and wander for the gain

of the many, for the welfare of the many, out of compassion for the world,

for the good, for the gain and the welfare of gods and men. Let not two of

you go the same way” (Vinaya 1:21).

9

Maier: Salvation in Buddhism

Published by Digital Commons @ Andrews University, 2014

2023-04-02

Original and Theravāda teaching indicate that a Buddhist can, for

the most part, help fellow seekers only by showing them an example of

dedication to meditation and self-denial. Mahāyāna teaching emphasizes

“compassion,” which involves aiding people in all areas of their lives,

even though such aid does not lead directly toward nirvāna. In Mahāyāna

Buddhism, salvation does not depend solely upon one’s own effort.

Good merit can be transferred from one person to others. No one can

exist by himself physically and spiritually. Mahāyānists regard the

egoistic approach to salvation as unrealistic, impossible, and unethical

(Cho 2000:81-84). They call themselves Mahāyāna because they see their

path as “larger and superior,” and they refer to Theravādan Buddhists

as Hinayana, that is the “narrow and inferior path.” Instead of seeking

Nirvāna just for oneself in order to become an arhat, the disciple of

Mahāyāna Buddhism aims to become a bodhisattva, a celestial being that

postpones his own entrance into parinirvāna (final extinction) in order to

help other humans attain it. Such a person swears not to enter Nirvāna

until he fulfills this noble mission. Here is a part of a bodhisattva’s vow:

I would rather take all this suffering on myself than to allow sentient

beings to fall into hell. I should be a hostage to those perilous places—

hells, animal realms, the nether world—as a ransom to rescue all sentient beings in states of woe and enable them to gain liberation. I vow

to protect all sentient beings and never abandon them. What I say is

sincerely true, without falsehood. Why? Because I have set my mind

on enlightenment in order to liberate all sentient beings; I do not seek

the unexcelled Way for my own sake. (Garland Sutra 23)

The bodhisattva beings help humans work out their liberation. Therefore, a bodhisattva (“Buddha-to-be”) rather than an arahat becomes the

ideal one seeks to achieve the religious discipline. The bodhisattva beings

help humans work out their salvation. In the process of obtaining this

goal, one realizes that all beings can benefit each other because they all

depend upon each other. Salvation depends on the help of others. A good

teacher can assist students on the path of salvation (Amore and Ching

2002:243-247; Cheng 1996:61).

Another savior concept that has been developed in all three stands of

Buddhism is the concept of the future Buddha, who at this time is living

in the Tusita (“joyful”) deva-world (Mahavamsa XXXII:72) and will return

sometime from between 500 to many millions of years after the death of

the Siddhartha Gautama or the historical Buddha. This future Buddha, or

Maitreya (“loving and kindly one”) will put salvation more easily within

the grasp of the people (Nanayakkara 2002:674, 675; Arthur 1997:43-57).

1

the most part, help fellow seekers only by showing them an example of

dedication to meditation and self-denial. Mahāyāna teaching emphasizes

“compassion,” which involves aiding people in all areas of their lives,

even though such aid does not lead directly toward nirvāna. In Mahāyāna

Buddhism, salvation does not depend solely upon one’s own effort.

Good merit can be transferred from one person to others. No one can

exist by himself physically and spiritually. Mahāyānists regard the

egoistic approach to salvation as unrealistic, impossible, and unethical

(Cho 2000:81-84). They call themselves Mahāyāna because they see their

path as “larger and superior,” and they refer to Theravādan Buddhists

as Hinayana, that is the “narrow and inferior path.” Instead of seeking

Nirvāna just for oneself in order to become an arhat, the disciple of

Mahāyāna Buddhism aims to become a bodhisattva, a celestial being that

postpones his own entrance into parinirvāna (final extinction) in order to

help other humans attain it. Such a person swears not to enter Nirvāna

until he fulfills this noble mission. Here is a part of a bodhisattva’s vow:

I would rather take all this suffering on myself than to allow sentient

beings to fall into hell. I should be a hostage to those perilous places—

hells, animal realms, the nether world—as a ransom to rescue all sentient beings in states of woe and enable them to gain liberation. I vow

to protect all sentient beings and never abandon them. What I say is

sincerely true, without falsehood. Why? Because I have set my mind

on enlightenment in order to liberate all sentient beings; I do not seek

the unexcelled Way for my own sake. (Garland Sutra 23)

The bodhisattva beings help humans work out their liberation. Therefore, a bodhisattva (“Buddha-to-be”) rather than an arahat becomes the

ideal one seeks to achieve the religious discipline. The bodhisattva beings

help humans work out their salvation. In the process of obtaining this

goal, one realizes that all beings can benefit each other because they all

depend upon each other. Salvation depends on the help of others. A good

teacher can assist students on the path of salvation (Amore and Ching

2002:243-247; Cheng 1996:61).

Another savior concept that has been developed in all three stands of

Buddhism is the concept of the future Buddha, who at this time is living

in the Tusita (“joyful”) deva-world (Mahavamsa XXXII:72) and will return

sometime from between 500 to many millions of years after the death of

the Siddhartha Gautama or the historical Buddha. This future Buddha, or

Maitreya (“loving and kindly one”) will put salvation more easily within

the grasp of the people (Nanayakkara 2002:674, 675; Arthur 1997:43-57).

1

2023-04-01

Salvation in Buddhism

Hindu Roots

Adherents of Hinduism (Warrier 2005:134), Buddhism, Jainism (Salter

2005:174; Narayanan 2002:164-166, 176-177), and Sikhism (Shackle and

Mandair 2005:1-19; Oxtoby 2002:139-141) do not believe in salvation in the

sense understood by most Westerners. They do not focus on Hell or Heaven as the end of a soteriological choice, but on knowledge (King 2005:149,

153). They believe in reincarnation (Buddhism rebirth) after death. According to this belief, one’s actions or karma allow one to be reborn as a

higher or lower being. If one is evil and has a multitude of bad actions,

one is likely to be reborn as a lower being. If one has a multitude of good

actions or karma, one is likely to be reborn as a higher being, perhaps a

human with higher status or in a higher caste (Padmasiri De Silva 1998:41;

King 1999:67, 123, 124, 172, 173). In fact, “birth and death are not the predestined fate of a living being but a ‘corollary of action’ (karma), as it has

been called by some. One who acts must sooner or later reap the effect;

while experiencing an effect, one is sowing seeds anew, thus causing the

next wave of life to be high or low according to the nature of one’s preceding actions” (Takakusu 1978:37).

Eventually, however, one is able to escape from samsāra, the cycle of

death and rebirth, through the attainment of the highest spiritual state. This

state is called moksha (or mukti) in Hinduism, and often is called Nirvāna

(Nibbāna) in Buddhism. This state is not one of individual happiness but

often a merging of oneself with collective existence (Dharmasiri 1986:19,

20). Nirvāna in the sutras is never conceived of as a place (such as one might

conceive heaven), but rather it is the antinomy of samsāra, which itself is

synonymous with ignorance (avidyā, Pāli avijjā). This said, “‘the liberated

mind (citta) that no longer clings’ means Nibbāna” (Majjhima Nikaya 2-Att.

4.68; Nanamoli and Bodhi 1995). Liberation therefore, in Buddhism is seen

as an end to suffering, rebirth, and ignorance (Dhammavihari 2003:160-

166) as well as the attainment of “Happiness, Moral Perfection, Realization

and Freedom” (Lily De Silva 1987:29).

Buddhism is actually a protest or radical movement directed against

the hallowed ritualism and sacrificial religion cultivated by the Brahmins

in Hinduism (Amore and Ching 2002:201-203; Lynn De Silva 1980:11-13).

As a substitute, it offers a system of moral training and mental discipline

leading to ultimate nirvāna. Siddharta Gautama, who discovered the

means by which deliverance from suffering can be achieved, is no longer

accessible; the Buddha is neither a “Savior” in the Judeo-Christian sense

or a “deva” (god) in the Hindu-Buddhist sense, nor is he alive. However,

Hindu Roots

Adherents of Hinduism (Warrier 2005:134), Buddhism, Jainism (Salter

2005:174; Narayanan 2002:164-166, 176-177), and Sikhism (Shackle and

Mandair 2005:1-19; Oxtoby 2002:139-141) do not believe in salvation in the

sense understood by most Westerners. They do not focus on Hell or Heaven as the end of a soteriological choice, but on knowledge (King 2005:149,

153). They believe in reincarnation (Buddhism rebirth) after death. According to this belief, one’s actions or karma allow one to be reborn as a

higher or lower being. If one is evil and has a multitude of bad actions,

one is likely to be reborn as a lower being. If one has a multitude of good

actions or karma, one is likely to be reborn as a higher being, perhaps a

human with higher status or in a higher caste (Padmasiri De Silva 1998:41;

King 1999:67, 123, 124, 172, 173). In fact, “birth and death are not the predestined fate of a living being but a ‘corollary of action’ (karma), as it has

been called by some. One who acts must sooner or later reap the effect;

while experiencing an effect, one is sowing seeds anew, thus causing the

next wave of life to be high or low according to the nature of one’s preceding actions” (Takakusu 1978:37).

Eventually, however, one is able to escape from samsāra, the cycle of

death and rebirth, through the attainment of the highest spiritual state. This

state is called moksha (or mukti) in Hinduism, and often is called Nirvāna

(Nibbāna) in Buddhism. This state is not one of individual happiness but

often a merging of oneself with collective existence (Dharmasiri 1986:19,

20). Nirvāna in the sutras is never conceived of as a place (such as one might

conceive heaven), but rather it is the antinomy of samsāra, which itself is

synonymous with ignorance (avidyā, Pāli avijjā). This said, “‘the liberated

mind (citta) that no longer clings’ means Nibbāna” (Majjhima Nikaya 2-Att.

4.68; Nanamoli and Bodhi 1995). Liberation therefore, in Buddhism is seen

as an end to suffering, rebirth, and ignorance (Dhammavihari 2003:160-

166) as well as the attainment of “Happiness, Moral Perfection, Realization

and Freedom” (Lily De Silva 1987:29).

Buddhism is actually a protest or radical movement directed against

the hallowed ritualism and sacrificial religion cultivated by the Brahmins

in Hinduism (Amore and Ching 2002:201-203; Lynn De Silva 1980:11-13).

As a substitute, it offers a system of moral training and mental discipline

leading to ultimate nirvāna. Siddharta Gautama, who discovered the

means by which deliverance from suffering can be achieved, is no longer

accessible; the Buddha is neither a “Savior” in the Judeo-Christian sense

or a “deva” (god) in the Hindu-Buddhist sense, nor is he alive. However,

2023-04-01

finally achieved the release from the cycle of rebirth (samsara) (Keown and

Prebish 2004:267; Skilton 1997:25; Armstrong 2001:187).

According to the Pali Buddhist scriptures, the Four Noble Truths (or

The Four Truths of the Noble One) were the first teachings of Gautama

Buddha after attaining enlightenment. Escape from suffering is possible

for those who accept and follow these Four Noble Truths which are traditionally summed up as follows: (1) life is basically suffering, or dissatisfaction (dukkha); (2) the origin or arising of that suffering (samudaya) lies

in craving or grasping; (3) the cessation (nirodha) of suffering is possible

through the cessation of craving; and (4) the way (magga) to cease craving and so attain escape from continual rebirth is by following Buddhist

practice, known as the Noble Eightfold Path (Nanayakkara 2000:262-264).

Theravāda Buddhism was one of the many schools that started shortly

after the death of the Buddha. It did not become popular until the third

century BCE, when the Indian emperor King Aśoka (or Ashoka) made

Theravāda Buddhism the official religion of his empire. In the same era,

King Aśoka sent missionaries, including his own son, Arahat Mahinda, to

Sri Lanka and other Southeast Asian countries. During the Muslim invasion of northern India around AD 1000, Buddhism began to die out in

India but started to flourish in other Southeast Asian countries such as

Sri Lanka, Thailand, Burma, Cambodia, and Laos (Lynn De Silva [1974]

1980:16, 17).

While Buddhism remains most popular within Asia, its various

branches are now found throughout the world. As Buddhism has spread

from its roots in India to virtually every corner of the world, it has adopted

and adapted local practices and beliefs. Various sources put the number of

Buddhists in the world at between 230 million and 500 million (Adherents

.com 2005; US Department of State 2004; Garfinkel 2005:88-109; Maps of

World 2009).

The Buddhist canon consists of a vast corpus of texts that cover

philosophical, devotional, and monastic matters. Each of the major

divisions of Buddhism has its own distinct version of what it considers

to be canonical scriptures (McDermott 1984:22-39). The Buddha did not

write down his teachings and rules of discipline. At the first council (543/2

BCE), two of Buddha’s travelling companions, Ananda and Upali, recited

the sutras (discourses on the doctrines) and vinaya (the monastic rules).

Later another disciple recited the systematic treaties. In the first century

CE, Buddhist monks in Sri Lanka wrote down the texts on palm leaves

(Nigosian 2008:179; Amore and Ching 2002:220; Lily de Silva 2007:26-39;

Warder 2000).

3

Maier: Salvation in Buddhism

Published by Digital Commons @ Andrews University, 201

Prebish 2004:267; Skilton 1997:25; Armstrong 2001:187).

According to the Pali Buddhist scriptures, the Four Noble Truths (or

The Four Truths of the Noble One) were the first teachings of Gautama

Buddha after attaining enlightenment. Escape from suffering is possible

for those who accept and follow these Four Noble Truths which are traditionally summed up as follows: (1) life is basically suffering, or dissatisfaction (dukkha); (2) the origin or arising of that suffering (samudaya) lies

in craving or grasping; (3) the cessation (nirodha) of suffering is possible

through the cessation of craving; and (4) the way (magga) to cease craving and so attain escape from continual rebirth is by following Buddhist

practice, known as the Noble Eightfold Path (Nanayakkara 2000:262-264).

Theravāda Buddhism was one of the many schools that started shortly

after the death of the Buddha. It did not become popular until the third

century BCE, when the Indian emperor King Aśoka (or Ashoka) made

Theravāda Buddhism the official religion of his empire. In the same era,

King Aśoka sent missionaries, including his own son, Arahat Mahinda, to

Sri Lanka and other Southeast Asian countries. During the Muslim invasion of northern India around AD 1000, Buddhism began to die out in

India but started to flourish in other Southeast Asian countries such as

Sri Lanka, Thailand, Burma, Cambodia, and Laos (Lynn De Silva [1974]

1980:16, 17).

While Buddhism remains most popular within Asia, its various

branches are now found throughout the world. As Buddhism has spread

from its roots in India to virtually every corner of the world, it has adopted

and adapted local practices and beliefs. Various sources put the number of

Buddhists in the world at between 230 million and 500 million (Adherents

.com 2005; US Department of State 2004; Garfinkel 2005:88-109; Maps of

World 2009).

The Buddhist canon consists of a vast corpus of texts that cover

philosophical, devotional, and monastic matters. Each of the major

divisions of Buddhism has its own distinct version of what it considers

to be canonical scriptures (McDermott 1984:22-39). The Buddha did not

write down his teachings and rules of discipline. At the first council (543/2

BCE), two of Buddha’s travelling companions, Ananda and Upali, recited

the sutras (discourses on the doctrines) and vinaya (the monastic rules).

Later another disciple recited the systematic treaties. In the first century

CE, Buddhist monks in Sri Lanka wrote down the texts on palm leaves

(Nigosian 2008:179; Amore and Ching 2002:220; Lily de Silva 2007:26-39;

Warder 2000).

3

Maier: Salvation in Buddhism

Published by Digital Commons @ Andrews University, 201

2023-03-31

"Listen to Me, O ? of Jacob,

And all the remnant of the ? of Israel,

Who have been upheld by Me from birth,

Who have been carried from the womb:

Even to your old age, I am He,

And even to gray hairs I will carry you!

I have made,and I will ?;

Even I will carry, and will deliver you.

And all the remnant of the ? of Israel,

Who have been upheld by Me from birth,

Who have been carried from the womb:

Even to your old age, I am He,

And even to gray hairs I will carry you!

I have made,and I will ?;

Even I will carry, and will deliver you.

2023-03-30

Some new guy named Michael McDonald stole this beat

2023-03-30

Bel bows down, Nebo stoops;

Their idols were on beasts and on the cattle. Your carriages were heavily loaded,

A burden to the weary beast.

They stoop, they bow down together;

They could not deliver the burden,

But have themselves gone into captivity.

Their idols were on beasts and on the cattle. Your carriages were heavily loaded,

A burden to the weary beast.

They stoop, they bow down together;

They could not deliver the burden,

But have themselves gone into captivity.